The past couple weeks here have been non-stop drizzling rain – not the nicest farewell I could have – but it reminded me of a

post from another of my favorite blogs, Futility Closet.

Shortly after Benjamin Franklin created the first lightning rod, the idea caught on in Europe as a

fashion accessory. There were umbrellas fitted with lightning rods (above), as well as hats, which trailed a wire for grounding. The information on these is a bit sparse, in particular whether they had ever been tested. This concerned me, since I saw some potential problems with the design, which I thought I'd explore today.

First, a quick explanation of how lightning rods work: During thunderstorms, charge collects in clouds. If enough charge builds up, it can overcome the resistance in the air, and create a channel down to the ground, where it discharges. This is

lightning, which can carry lots of charge at high speed. Electricity takes the path of least resistance, and since humans and animals carry a lot of salty water, that makes us appealing routes to the ground. Tall buildings can also make good conductors, but since lightning carries so much energy, it can start fires. To protect ourselves, and our homes, we can make even better channels by topping buildings with a metal rod that connects directly to the Earth through a wire. Based on this, the lightning rod apparel doesn't seem unreasonable, but let's look at some issues.

Ground Current

For real lightning rods, the grounding wire is buried several feet deep to better distribute the charge, but that wouldn't be possible with a rod you carry with you. Instead, the wire just drags behind you, but that's no different from lightning striking the ground near you. Lightning carries a lot of charge, and it takes some space to dissipate, which can be just as dangerous as the initial strike. The

National Weather Service webpage illustrates this with a charmingly-90s, yet still horrifying, animated GIF:

According to the

Washington Post, ground current can be dangerous as far as 60 feet from the initial strike, so you'd need an awfully long tail on your umbrella/hat, not to mention the danger to anyone else who happens to be near the contact point.

Melting Wire

Since these are fashion accessories we're talking about, the Wikipedia article above mentions that the grounding wire was silver, but that could get expensive.

One site I found lists the gauge for a grounding wire as 2 AWG, or about a

quarter inch. There's also the problem that silver has a lower melting point than copper,

961.78 °C. That made me curious whether you'd be trading electrocution for being sprayed with molten silver.

The energy absorbed by the wire will be

where

I is the

current,

𝜌 is silver's

resistivity,

l is the length of the wire,

A its area, and

t is the

duration of the strike. Using those values, along with a

normal (rather than rope-sized) silver chain, and a height of 1.8 meters, I come up with

195 Joules, which is nowhere near enough to melt even a thin chain.

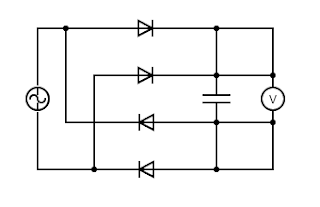

Magnetic Field

So at this point, you're still dead from the ground current, but your relatives will be able to salvage your silver chain. What about your smartphone? When current flows through a wire, it produces a magnetic field, according to

I couldn't find info for smartphones, but according to this

site, credit cards could be damaged at a distance of

63 centimeters, and pacemakers at

25 meters! I'm not sure whether the short duration of the bolt would change these calculations, but it still doesn't seem like you or your electronics would be safe in a thunderstorm, even if you are wearing the height of 18th century fashion.

Big thanks to

Futility Closet for pointing out this fleeting trend! I'm sure we would never use new technology in such a frivolous way, right?